The sovereignty of Switzerland

3 October 2022

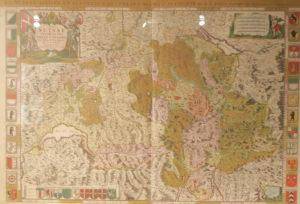

The history of the sovereignty of Switzerland knows many dates, myths and (historical and political) discussions. The territory of present-day Switzerland was still part of the Holy Roman Empire in the 15th century.

In the 19th century, this territory (except Tarasp (1803), Rhäzuns (1819) and Neuchâtel (1856) became sovereign in 1815 and/or 1848. The period between the 16th and 18th centuries (until 1798, 1803, and 1815) is unclear.

The Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire from around 1530 extended over territories which today cover more than ten sovereign states (Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, Austria, France (Lotharingen, Franche-Comté, (High) Savoy, Elzass), Germany, Czech Republic, Slovenia and territories in Croatia and Poland).

The Emperor

Spain, Hungary, Sicily, and Sardinia were linked in a personal union. The Habsburg dynasty delivered 1438-1806, almost without exception the emperors. This Empire, its emperors and the Pope also embodied the Latin Christianitas.

The Empire was formally a political and legal entity. The Imperial Chamber Court (Reichskammergericht in Worms, Speyer and Wetzlar), the Court Council (Hofrat) in Vienna and the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) were the courts and legislators.

The territory had many ecclesiastical and secular regional and local rulers: bishoprics, abbeys, duchies, counties, and imperial cities (Reichstädte).

The (different) local laws and customs were often decisive. Political or legal unity did not exist. Three factors are important in this respect.

The emperor’s monopoly on the use of force for peace and justice (relevant for the Swiss Confederation in 1415 (conquest of Aargau), 1460 (conquest of Thurgau) and 1474-1477, the Burgundian Wars, with imperial permission), secondly the levy of taxes and thirdly the prestige of the Empire.

The Eidgenossenschaft or Confederation

Switzerland did not exist at that time, just local alliances between cities and Orte, the predecessors of the cantons. The well-known alliance of the three Orte (cantons) around 1291 and subsequent alliances between other cities in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries mark the beginning of the state-building process.

Such alliances, such as the Alsatian Zehnstädtebund or Dekapolis, the Hanseatic League in Northern Europe or the Swabian League in Southern Germany, were common then.

Switzerland’s politically most crucial alliance was between the imperial cities of Zurich, Bern, Lucerne, Fribourg, and Solothurn in and after 1351. The outcome was the Confederation (Eidgenossenschaft) of thirteen towns/ Orte and their Untertanengebiete in 1513.

This Confederation existed until 1798 and survived all other alliances. What made the Confederation an exception and a particular case?

The imperial government of the Holy Roman Empire and powerful kingdoms (France, Spain, England, Poland-Lithuania, and Scandinavia ) were the dominant factors in the formation of the states between 1495 and 1648. The Empire knew many regional and local secular and ecclesiastical rulers in Switzerland.

The many imperial cities and imperial privileges are essential. Imperial cities were autonomous, highly privileged communities, such as Basel, Bern, Zurich, Fribourg, Lucerne, Zug, Schaffhausen, Rapperswil, Geneva, St. Gallen, Stein am Rhein and Solothurn.

This region had many other imperial cities (Besançon, Colmar, Strasbourg, Rottweil, Mulhouse, Augsburg, Konstanz, for example) and city federations (Dekapolis, Schwäbischer Bund, Eidgenossenschaft). More than 90% of all imperial cities were located in the southwestern quarter of the Empire.

The Orte/ cities of the Eidgenossenschaft and their subjected territories (Untertanengebiete) and allies (Zugewandte Orte) were seamlessly connected, in contrast to the Alsatian Zehnstädtebund and the Schwäbischer Bund.

Moreover, the Eidgenossenschaft and the mountain passes, rivers, and north-south connections formed an area for trade, passenger and military transport.

Hence Grisons or Graubünden (the Republic of the three leagues of the Gotteshausbund, Zehngerichtebund, Oberer/Grauer Bund, 1524) and the cantons Uri, Schwyz, Glarus, and Unterwalden showed interest in (military) cooperation with the cities.

These (commercial) interests were ultimately more important than the many religious (after 1525), political and territorial differences.

For example, the cantons in Central Switzerland were mainly interested in Italian territories, and Bern (Solothurn and Fribourg) was interested in the conquest of Western Switzerland and beyond.

Important moments were the conquest of Aargau (1415), Thurgau (1460), the Burgundian wars (1474-1477), the Swabian war (or Swiss war, Engadin war or Tyrolean war, depending on the perspective, 1499), the conquest of Italian territories (1512), the expansion of the Eidgenossenschaft to 13 members in 1513, the conquest of Vaud by Bern and Fribourg (1536) and the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

However, these facts were not decisive for the creation of the sovereign federation. The 13 cantons of the Eidgenossenschaft remained sovereign until 1798, and the Confederation was not yet a new European state, although it was regarded and treated as such by other countries.

1798-1848

The years 1798-1815-1848 were decisive. However, the roots of sovereignty go back centuries, and 1291 (fact, myth or mixture) is an appropriate symbol of sovereignty. The speculation that ‘matters could have gone differently’ is not relevant from a historical point of view.

(Source: B. Marquardt, Die alte Eidgenossenschaft und das Heilige Römische Reich (1350-1798). Staatsbildung, Souveränität und Sonderstatus am alteuropäischen Alpenrand, Zurich 2007).